“Cows are just big dogs. They’re so playful and sweet,” says Amber Graves. “I love them because they are a piece of where I grew up and what I call home.”

At 26 years old, Amber is the fifth generation to farm at Morning Fresh Dairy in Bellvue, Colorado, alongside her older siblings Bryan, Allyx and Trevor. The family has sold milk in their community since 1894, launching Noosa Yoghurt—now a popular brand across the nation—in 2009, and opening Howling Cow Café in 2014. All four of the Graves children left home as young adults to pursue other careers, but slowly they were all drawn back to the farm.

Today, Amber’s role is “continuous improvement,” which includes working the home delivery route, developing new products and talking with everyone from legislators to the media to tourists about what it means to be a family farmer.

This also includes fighting misconceptions all farmers face—especially those who work in livestock.

“People say, ‘You treat your cows badly,’ and that honestly hurts my heart,” says Amber. “More education would go a long way … rather than the random video they watched on an Instagram reel of this one bad dairy. So I always say, ‘Come take a tour, see what we do.’”

Morning Fresh Dairy has had a core philosophy of humane animal treatment and sustainable farming practices for more than a century. According to Amber, economic and environmental sustainability go hand-in-hand: Raising happy cows has been a business imperative.

“A happy cow just flat-out means they’ll produce more. The core of your business is the cows, so you’ve got to keep them happy,” says Amber.

In conventional dairy production, it’s typical to send young female cows to feedlots until they’re pregnant. But cows at Morning Fresh Dairy stay on the farm for their entire lives. That way, the Graveses can control how they’re cared for and fed. Sick cows are separated, treated, fully recovered and tested before rejoining the healthy cows.

“The Graveses look to do everything in the best way possible,” says Frank Garry, professor at Colorado State University and expert coordinator with AgNext, a collaboration working on sustainable solutions for animal agriculture. Garry has known the Graveses for 35 years. While partnering across a range of research studies, he’s watched the operation grow and evolve.

“As they built their buildings, they focused on creating the best quality care for their animals,” says Garry. This means creating a clean, low-stress environment for birthing and ensuring their animals are kept comfortable throughout their lives.

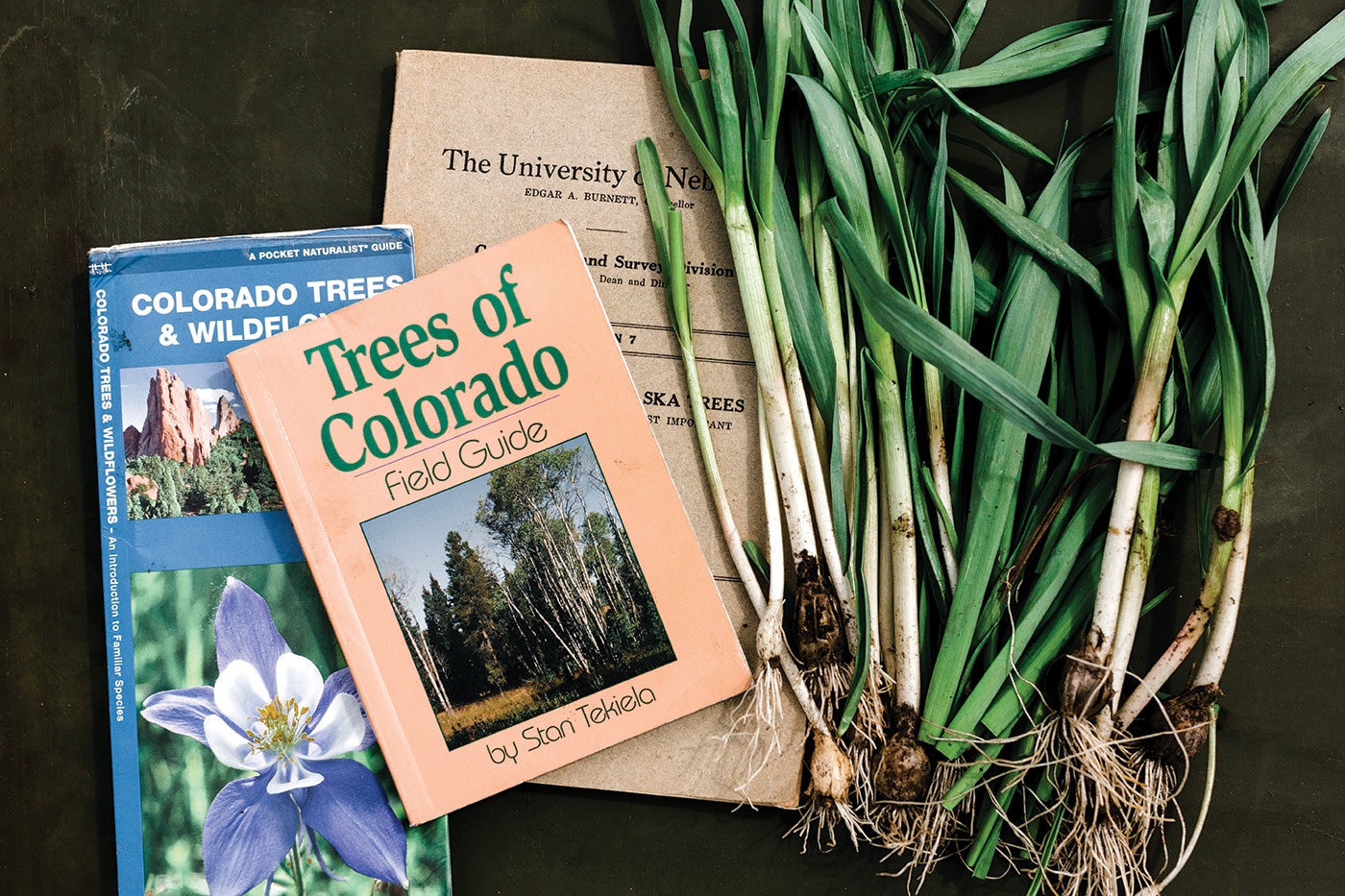

In the fields, conventional farming uses a practice called tilling, which helps control weeds and pests by turning the soil over before planting. Amber says that while tilling does have some benefits, it disrupts soil structure and contributes to erosion. The Graveses instead plant tubular radishes with bulbs that can reach a foot deep, which naturally do the work of breaking up the soil below the surface.

“When your radish is doing that for you, you use less diesel [without tilling], it keeps the bugs happier and you keep more carbon in the soil instead of releasing it into the atmosphere,” says Amber. “And then the cows get to eat it, too.”

The Graveses never use pesticides. They focus on soil-health-building practices like regenerative cover cropping—planting crops to protect the ground over the winter months. This sequesters nutrients in the soil instead of adding them through synthetic fertilizer. And Amber says it’s working—they take soil samples multiple times a year to track the soil quality and improvement.

Pairing these sustainable practices with modern technology has allowed the Graveses’ business to flourish, says Amber. They use RFID tags to track when their cows are milked, how much milk they’re producing and health data. Managers receive an alert if one of the cows has a sudden or uncharacteristic dip in milk production, so they can check on the animal and catch any issues earlier.

“Now that we know more through all the data, we can look at things differently,” says Amber. Rather than reacting to the “chaos of the day,” they have the information and equipment to take a proactive approach to cow, soil and farm health. “We’re able to do a lot more.”

And having the whole family working on the farm has been an enormous help—the Graveses have all hands on deck.

“Because the kids have stayed on the farm, it means they have places they can focus attention. It’s done better because of their oversight; they really care about what they’re doing,” says Garry.

This was especially true when the Covid pandemic hit. After the lockdowns in 2020, while Morning Fresh Dairy had a waiting list for home delivery for the first time, their wholesale customers couldn’t use their normal orders of cream.

“Cream is like the gold of milk,” says Amber. “And usually, we just never have enough. But we were dumping cream just because it was going bad …. It hurt my heart watching that go down the drain.”

So Amber got to work. She started using the extra cream to make ice cream during the pandemic, and today, Ummber’s Premium Ice Cream can be found in local coffee shops and grocers.

Now, Amber is working on a new bottle design for wholesale customers that want reusable materials but have trouble with glass bottles breaking. She’s investigating how aluminum foil caps can be used to reduce plastic use. And she also led a partnership with students at the University of Colorado to turn farm manure into energy.

Resulting from the students’ work, Morning Fresh Dairy is now in the preliminary stages of installing an on-site anaerobic digester. This will break down the farm’s manure and food waste using microorganisms to produce biogas, then convert it into clean energy. The remaining materials not used for energy will be used for crop fertilizer.

As she grows into her role, Amber sees Morning Fresh Dairy as an educator for the community.

“I never fully realized how much of a gap there is between people and knowing where their food comes from,” says Amber. The farm started hosting tours in 2018, and she describes watching people’s eyes light up when they see the connection between the cows in the field, the warehouses of the processing equipment and a cup of fresh milk, yogurt or ice cream.

“One thing I love about the Front Range is people just really value local,” says Amber. But for her, consumer education must also include thinking critically about the role of agriculture in the community.

“All of us, rural and urban, call this place home and we need to work together to make sure we can all live together and have a productive local economy,” says Amber.

Personally, Amber wants to be a voice for agriculture within her county, figuring out ways to work together that are good for constituents, farmers and the environment alike.

She serves on the Agriculture Advisory Board for Larimer County, where she and other farmers find ways to use leftover agricultural biomass, among other initiatives. She’s completed the Water Literate Leaders of Northern Colorado program at Colorado State University, and she hopes to be involved in the Poudre Food Partnership to help build a more equitable, vibrant and resilient local food system.

“There are all these decisions being made that affect the future growth of our county and community, but they only have a small group of stakeholders. There’s not much ag, there’s not much diversity,” says Amber.

When it comes to water use in the area, for example, Amber notes that water from crop irrigation at Morning Fresh Dairy flows back into the river and through Fort Collins. The river would lose that return flow if the farm were converted into homes or businesses.

“We are in a desert. There’s limited water, and as more people move here, we must figure out a good way to have both,” says Amber. “So, I think farmers being at those conversations is important.”

Morning Fresh Dairy and Noosa support conservation efforts like the Watson Lake Fish Bypass project, which built a fish ladder to allow wild longnose suckers and rainbow trout to migrate through river dams and access spawning grounds. Allowing the fish to move more freely and reproduce helps to restore natural ecosystems and support river health—and that benefits everyone in the community.

“If we educate people … I think there will be a lot more community involvement in that,” says Amber. She already sees an appetite for learning more about the nuances of food production and agriculture’s role in the community.

“People are just curious; they want to know more. People love when they know something is growing right here in Fort Collins because that’s their neighbor. It might be $1 cheaper somewhere else, but who knows where that money is going?” says Amber. “So that makes me hopeful.”